The poverty lines being used by South African officialdom could understate the country’s poor population by nearly 5 million people.

New research from the University of Cape Town’s Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (Saldru) puts 63% of the country in the camp of the “poor”, compared with the latest Stats SA figures released in January of 53%.

It isn’t a quibble about what being “poor” means. Both are based on an average 2 100 kilocalorie-per-day diet and the same Stats SA survey data.

Instead, the new work by Saldru’s Josh Budlender, Murray Leibbrandt and Ingrid Woolard, working closely with Stats SA, shows how what we know about the country can be skewed by extremely technical methodological decisions.

Poverty lines turn out to be like sausages: you might sleep easier not knowing how they are made.

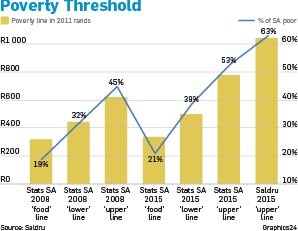

The line the Saldru team came up with was R1 042 per person, per month in 2011 – which amounts to R1 307 by now due to inflation. The Stats SA line was R779 a month in 2011, which is about R985 now.

Stats SA’s new line was already far higher than the one it had produced in 2008, which rendered only 45% of South Africans “poor” in 2011 (see graphic).

Most of the difference comes from a technical decision by Stats SA on how to clean “outliers” – people whose spending patterns are judged to be unrealistic – out of the data. If Stats SA hadn’t taken what the Saldru team says was an overcautious approach, it would have produced a poverty line of R1 206 in current money terms, says Budlender.

The Saldru work also attacks the traditional distinction between an “upper”, “lower” and “rock-bottom” food poverty line that appears in most official reporting on poverty.

While the minimal food poverty line, currently about R444, serves an intuitive purpose, the intermediate “lower” poverty line doesn’t really make very much sense, says Budlender.

The food line allows you to say how many people have “so little money that even if they spent all of their money on food, they still wouldn’t achieve sufficient caloric intake”, says Budlender.

The “upper” poverty line amounts to the real observed expenditure on food and non-food items of people who consume more or less exactly this amount of calories.

It avoids the problematic tendency of earlier generations of poverty lines that simply prescribed what its creators deemed to be the correct necessities of life (see box).

“There is no equivalent explanation of the lower bound, so it doesn’t really serve any purpose,” says Budlender.

“The only justification we can imagine ... is that a researcher views the upper bound as too high and the food poverty line as too low for practical use.”

That kind of “ad hoc decision, based on a purely subjective basis” is, however, precisely what the complicated work to create poverty lines is meant to avoid, says Saldru. The “lower” line is incidentally the one that the National Development Plan uses to set poverty-eradication targets.

The uncertainty about how many people are “poor” raises questions about what the measure is to begin with. The point, says Stats SA in its report this year, is to enable “planning for poverty reduction”. It explicitly discourages confusing the line for recommended wage levels, something pre-1994 poverty measures were explicitly designed to do.

By and large, this involved “scientifically” justifying low wages for black people. Stats SA poverty lines are not “official” lines, but are also used to gauge progress against the Millennium Development Goals.

Other researchers are using the Saldru line to establish “working poverty” lines, which imply a logical connection to wage-setting, even though the people involved warn against this.

Poverty lines are always arbitrary to some extent, says Budlender. “They are subsistence measures, and envision quite a low standard of material welfare.”

What it takes to be poor

The lines are all fundamentally based on energy intake of 2 100 kilocalories per day.

Although it seems scientific, choosing an energy intake to base poverty on can be relatively arbitrary, with huge effects on the ultimate findings.

The 2 100-kilocalorie target comes from the World Health Organisation’s guide for “typical” developing country inhabitants. These are so-called small calories, and a kilocalorie is equal to what normally just gets called a calorie.

In 1985, Debbie Budlender (the aunt of the co-author of the new research) published a scathing interrogation of the then authoritative, but ultimately racist and incoherent, South African poverty lines tied to wage-setting for black people.

Among other things, she attacked the setting of calorie recommendations on the basis that they seemed designed for an office worker engaged in “light activity”, not someone who did physical work.

At the time, some South African companies based their labour policies on presumed worker needs of up to double the 2 100 kilocalories per day.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners